Analogous structures provide a fascinating glimpse into the evolutionary tapestry of life, showcasing how disparate organisms can evolve similar traits in response to comparable environmental pressures. Unlike homologous structures, which arise from a common ancestor, analogous structures developed independently in different lineages. This phenomenon is a cornerstone of convergent evolution, presenting scholars and enthusiasts alike with resplendent examples of functional adaptation across the natural world. In this article, we delve into various instances of analogous structures, dissecting their intriguing characteristics and the evolutionary significance behind their development.

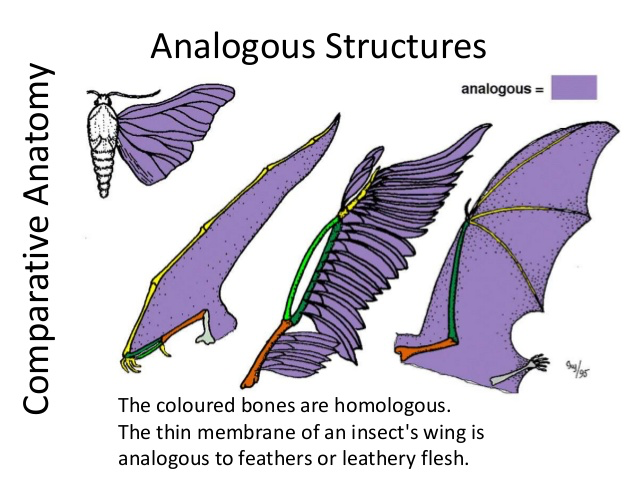

The most emblematic example of an analogous structure can be witnessed in the wings of birds and bats. While both serve the essential function of flight, they belong to markedly different taxa. A bird’s wing is an intricate modification of the forelimb with feathers that facilitate aerodynamics. Conversely, a bat’s wing manifests as an extended skin membrane that stretches between elongated fingers. Despite their structural differences, both wings accomplish the same purpose, highlighting how evolution finely tunes organisms to thrive in similar niches. This duality exemplifies how evolution can mold distinct anatomical features to reach parallel functional outcomes.

Moving beyond the animal kingdom, analogous structures can also be observed in the plant world. One such instance is the similarity between the Australian Eucalyptus tree and the North American cacti. Both have evolved to exhibit remarkable adaptations for water conservation in arid environments, but their structural foundations are vastly different. Eucalyptus trees possess thick, waxy leaves that minimize water loss, while cacti have adopted a reduced leaf structure with photosynthetic stems. These evolutionary trajectories, though originating in divergent lineages, produce analogous adaptations that enhance survivability in similar habitats.

Another quintessential illustration of analogous structures is found in the eye. The compound eyes of insects and the camera-like eyes of vertebrates serve the same primary purpose: vision. However, the architectural intricacies differ significantly. Insects feature a myriad of ommatidia, enabling a broad field of vision, while vertebrate eyes possess a singular lens capable of focusing light accurately into the retina. Despite these differences in construction, both eye types efficiently translate visual stimuli into neural signals, showcasing evolutionary problem-solving at its finest.

The creation of analogous structures is frequently driven by the selective pressures imposed by the environment. For instance, the streamlined bodies of dolphins and sharks serve as a testament to convergent evolution in aquatic settings. Dolphins, mammals, have evolved to have a blubber layer for insulation, while sharks, being fish, rely on a unique cartilage structure. Nevertheless, both exhibit fusiform shapes that reduce drag, propelling them gracefully through water. This shared trait is a brilliant example of how function can supersede lineage in the grand narrative of evolution.

Additionally, the phenomenon of analogous structures extends into the realm of behavior. The ability of wolf-spider and tarantula to display remarkable hunting techniques reflects a similar ecological role, despite their distant evolutionary paths. Both employ ambush tactics to capture prey—a convergence of behavior aimed at maximizing their predatory efficiency. Such behavioral similarities can often be overlooked, yet they underscore the notion that evolutionary advantage transcends the physical morphology.

Analogous structures also find expression in the realm of locomotion among diverse creatures. A striking example lies in the legs of insects and the flippers of seals. Both adaptations serve the common purpose of facilitating movement in their respective environments—land and water. Insects possess jointed, segmented legs ideal for navigating diverse terrains, while seals exhibit powerful flippers that enable swift swimming. Again, we see that necessity breeds similarity, irrespective of an organism’s ancestry.

The exploration of analogous structures illustrates the remarkable versatility of life. Evolution does not follow a prescriptive blueprint; rather, it is a meandering journey where organisms are sculpted by necessity and environmental demands. As adaptations arise, they elucidate the shared challenges that different species encounter, despite evolutionary distances. These structures serve as poignant reminders of nature’s ingenuity and the intricate web that connects all living things.

Moreover, understanding analogous structures enriches our comprehension of evolutionary biology and the mechanisms driving the vast diversity of life on Earth. Such knowledge encourages conservation efforts, underscoring the importance of protecting habitats where these remarkable adaptations flourish. The myriad ways life has evolved in parallel is a story still unfolding, interlacing threads of shared experiences across ages.

In summation, the study of analogous structures showcases the dazzling complexities and dynamism of evolution. Whether through the wings of birds and bats, the eyes of insects and vertebrates, or the locomotion strategies of diverse species, each example emphasizes the power of adaptation in shaping life. By recognizing these structures’ significance, we gain invaluable insight into the resilience and ingenuity of the Earth’s myriad organisms, reminding us that, despite our differences, we are all part of a grand, interconnected narrative of survival and evolution.