What comes to mind when you hear the term “hardness”? Is it a daunting challenge or a perplexing puzzle? Hardness, particularly in the context of materials, is a critical factor that engineers, manufacturers, and metallurgists must consider. In this exploration, we dive into the specifics of hardness ratings, with a particular focus on the intriguing range of 30–35 HRC. So, what exactly does it mean, and why is it significant?

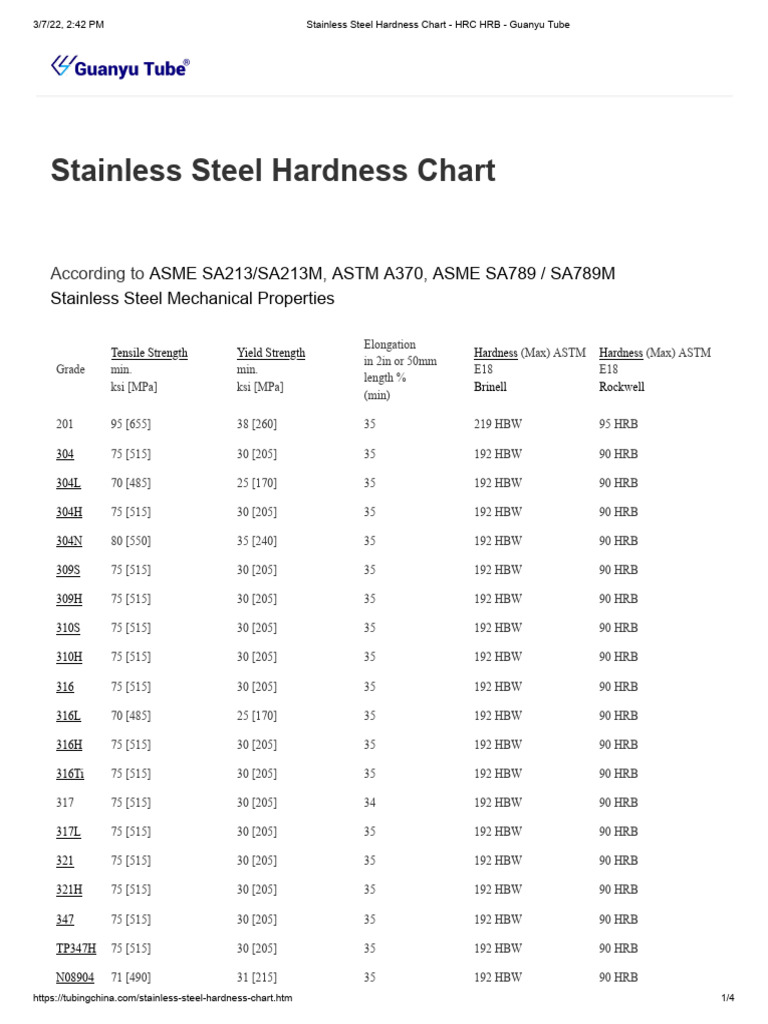

First, let’s unpack the term HRC. The HRC scale refers to the Rockwell hardness scale C, a method for quantifying a material’s hardness. It is widely used for metals and alloys, providing insight into their strength, durability, and suitability for various applications. This scale operates on a relatively straightforward principle: it measures the depth of penetration of an indenter under a large load compared to the penetration made by a preload. In simple terms, the harder the material, the less it will deform under pressure.

Within the realm of hardness measurement, the range of 30–35 HRC presents a unique positioning on the hardness scale. An HRC of 30 denotes a soft yet resilient material, while a 35 HRC suggests more robustness without transitioning into extremes found in harder materials. To visualize it, picture a scale where the materials only a mere step apart can serve dramatically different purposes. But what kinds of materials typically fall within this hardness range?

Commonly, steels treated through processes like oil quenching fall within this category. Particularly, medium carbon steels—those containing approximately 0.3% to 0.6% carbon—exhibit hardness within the 30–35 HRC range after appropriate heat treatment. With the right tempering process, these materials achieve a perfect balance of toughness and ductility. The attributes of steel in this range lend themselves beautifully to various applications, from automotive components to structural elements in buildings.

Now that we understand the nature of materials sitting at 30–35 HRC, it’s crucial to discuss why this range is particularly desirable. What characteristics make these materials appealing for engineers looking to strike a balance between flexibility and strength? Here are pivotal attributes to consider:

- Toughness: Materials at this hardness level tend to withstand impacts well, making them ideal for applications requiring high resistance to fracture or shock. If you were to drop a heavy object on a component made from 35 HRC steel, chances are it would absorb the energy without succumbing to catastrophic failure.

- Ductility: Not too hard to the point of being brittle, materials in this range can deform under stress without breaking. A ductile material can be formed into intricate shapes, which is a huge advantage in manufacturing processes.

- Wear Resistance: While not as wear-resistant as harder materials, steel at 30–35 HRC can endure moderate wear, making it suitable for numerous applications where parts interact with each other, such as gears and bearings.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Achieving this hardness level often involves relatively simple heat treatment processes that keep production costs manageable without sacrificing performance.

At this juncture, let’s delve deeper into applications utilizing materials within this hardness range. For instance, many automotive and machinery components are crafted from medium carbon steels treated to reach approximately 30–35 HRC. These components typically include:

- Fasteners: Nuts and bolts often require a balance of strength and ductility to ensure they can securely hold components together without breaking under stress.

- Gears: A gear set must endure operational wear while maintaining its shape, making medium carbon steel an attractive option.

- Shafts: The integrity of a shaft must be maintained even when subjected to varying loads; thus the right hardness can aid in maintaining performance longevity.

Now, imagine this scenario: You’re considering utilizing a 35 HRC steel for a new product design. How do you proceed? Here lies the intellectual challenge that invites creativity and technical acumen. Testing the selected material’s performance through stress tests and simulations ensures it meets the operational demands. However, achieving the correct hardness may require meticulous control over the heat treatment process.

Moreover, it’s imperative to remember that while hardness plays a vital role, it is not the sole attribute defining material suitability. Other factors such as tensile strength, fatigue resistance, and environmental conditions must also be carefully evaluated. Conducting a comprehensive material analysis can shed light on the best candidate for your specific application and its long-term performance. The challenge is clear: can you navigate the intricate interplay of these characteristics to select the right material for your next project?

In conclusion, the realm of 30–35 HRC hardness offers a treasure trove of opportunities for engineers and designers alike. The delicate balance between strength, ductility, and wear resistance makes these materials invaluable across a plethora of applications. Understanding their properties and how they interact with various stresses can help usher in innovations that push the boundaries of what’s possible. So, the next time you encounter a material within this hardness range, consider the questions and challenges it presents. How will you harness its potential?