The intricacies of meter in poetry are akin to the rhythmic heartbeat of a living organism, underscoring the emotional resonance and musicality that brings words to life. Meter propels a poem from mere text to an experience, beckoning readers into its lyrical embrace. In examining the rich tapestry of meter, one may easily discover how it shapes meaning, evokes emotions, and crafts a distinctive auditory experience. This exploration into meter in poetry unveils not just the techniques used, but also the profound depth they lend to literary artistry.

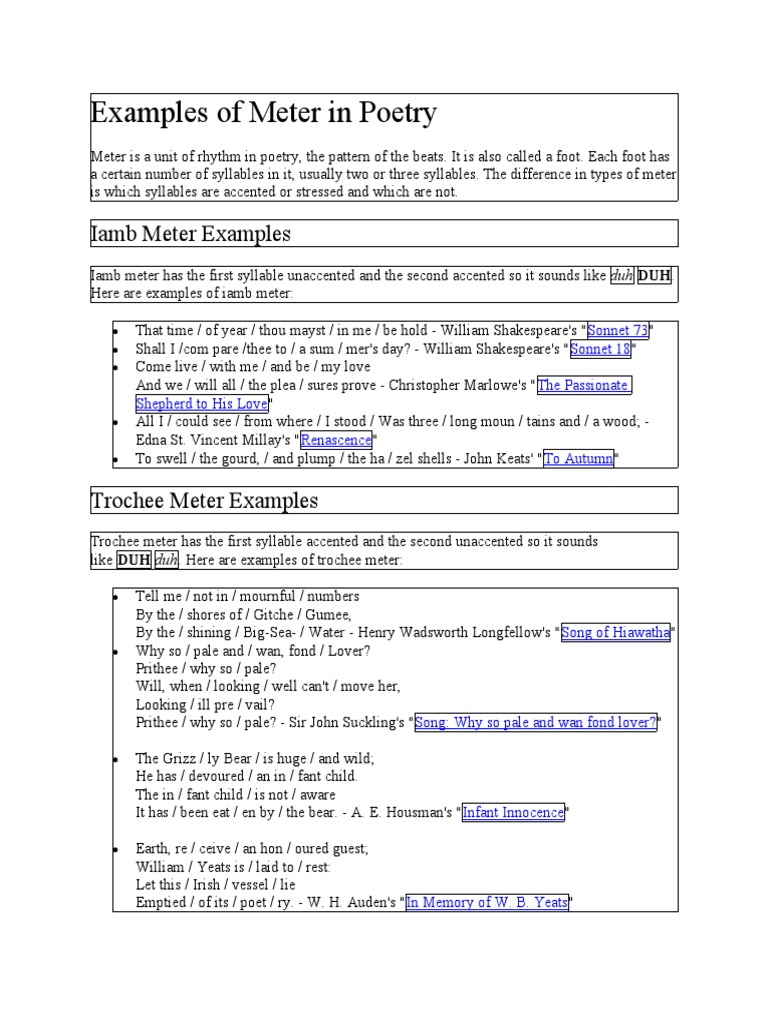

At its core, meter is defined by the structured arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables. It creates a rhythmic foundation that can elicit a myriad of emotional responses. With varied measurements such as iambs, trochees, anapests, and dactyls, poets have a cornucopia of tools at their disposal. Each metrical foot conjures an array of evocative images, allowing poets to engage the reader’s imagination through sound as much as through meaning.

For instance, consider the iambic pentameter—a quintessential meter that has stood the test of time thanks largely to the works of poets like William Shakespeare. This meter consists of five iambs per line, each comprising an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (“da-DUM”). It’s a cadence that mimics the natural rhythm of human speech, offering a sense of familiarity while also enhancing the narrative’s lyrical quality. An example of iambic pentameter can be found in Shakespeare’s sonnets. The opening line of Sonnet 18, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” underscores the intimate connection between meter and imagery. The steady pulse complements the poem’s themes of beauty and transience, pulling readers into a poignant reflection on mortality.

Moving beyond the familiarity of iambic meter, we find the potent allure of trochaic meter. Trochees invert the typical iambic flow, featuring a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one (“DA-dum”). This switch invigorates the lines, introducing a different kind of energy. A prime example can be garnered from the opening of Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha.” The trochaic tetrameter creates a sonorous and almost incantatory effect, encapsulating the majestic spirit of storytelling and folklore, drawing readers into a world that feels both ancient and immediate.

In addition to traditional meters, free verse has emerged as a powerful form that liberates poets from the constraints of structured rhythm. While lacking a consistent metrical pattern, free verse allows poets to infuse their work with a conversational tone that resonates with contemporary readers. Walt Whitman brilliantly utilized this form in “Leaves of Grass,” forging a unique soundscape that reflects the pulse of American life. Through the irregular rhythms and varied line lengths, emotional cadences ebb and flow, resonating with the chaotic beauty of human existence.

What distinguishes meter from mere rhythm is its ability to reinforce thematic elements within a poem. The interplay between sound and meaning creates a rich tapestry of associations. For instance, the relentless beat of a poem may evoke urgency or tension, while a gentle cadence can imply tranquility or reflection. Consider Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” Utilizing iambic tetrameter, Frost crafts a soothing rhythm which contrasts starkly with the poem’s weighty themes of duty and contemplation. The cadence invites tranquility as the narrator pauses to admire the serene beauty of the snow-draped woods, emphasizing the allure of nature against the backdrop of worldly obligations.

Moreover, meter can serve as a vehicle for metaphors, enriching the reader’s comprehension of abstract concepts. The world of poetry is replete with innovative metaphors that transcend the literal, inviting interpretation through rhythm. Take John Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” characterized by a sophisticated use of iambic pentameter interspersed with rich imagery. The steady beat of the poem parallels the desire for transcendence, while the nightingale itself becomes a metaphor for immortal beauty. The interplay of sound and meaning encapsulates the dichotomy of human experience—the longing for permanence in the face of inevitable mortality.

The unique appeal of meter lies in its paradoxical nature—it is at once a musical structure and a flexible conduit of expression. It can create forms that beckon the reader into a structured experience while simultaneously allowing for profound emotional exploration. Ultimately, the choice of meter is an artistic decision that can transform the entire reading experience, creating an unforgettable connection between the poet and the audience.

As we engage with the ethereal beauty of poetry, understanding meter not only deepens appreciation but also enriches our interpretation of the text. Whether through the familiar rhythms of iambs and trochees or the liberated flow of free verse, meter serves as a harmonious partner to meaning—a conduit through which the pulse of life, emotion, and thought is transmitted. In exploring these varied meters, we not only gain insight into the intricacies of poetic form but also discover the resonant layers that make poetry an enduring and vital expression of the human experience.