Convection is a fundamental process that shapes our understanding of heat transfer, distinctly characterized by the movement of fluid—whether it be liquid or gas—facilitating the exchange of thermal energy. This phenomenon can be observed in various environmental processes, cooking techniques, and even within the interiors of celestial bodies. A quintessential example of convection is the heating of water in a pot. As mundane as this may seem, the underlying mechanics of convection provide insights into broader scientific principles that govern our world.

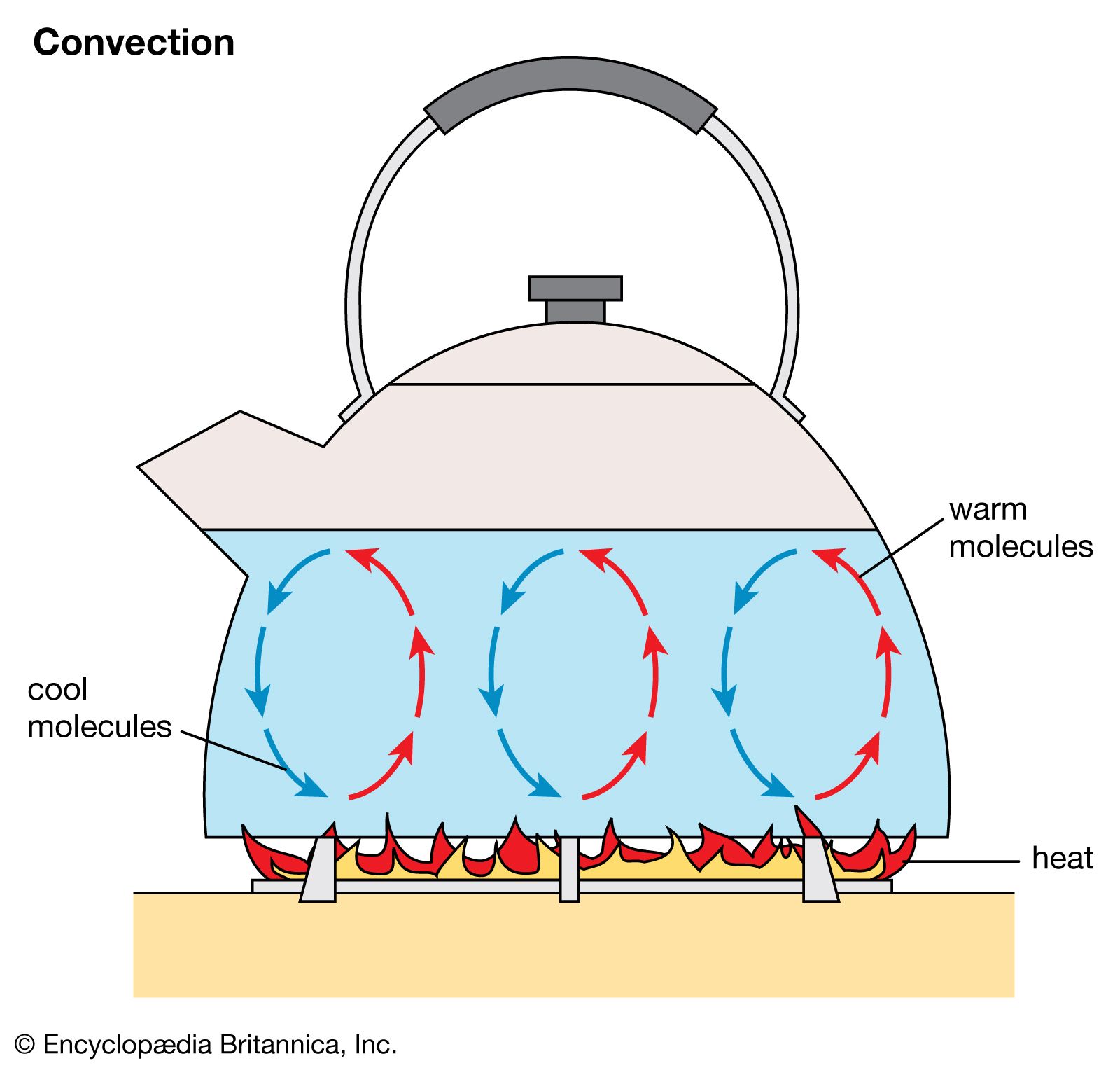

To delve deeper into this common observation, consider a simple scenario: filling a pot with water and placing it on the stove. Initially, the water at the bottom of the pot is in contact with the heat source, leading to an increase in temperature. As the water heats up, it becomes less dense than the cooler water above it. This decrease in density allows the heated water to rise, while the cooler, denser water sinks to replace it. This constant cycle creates a convection current, effectively distributing heat throughout the pot until the entire body of water reaches a uniform temperature.

The visual dynamics of this process are mesmerizing. One can often see swirls and eddies forming as the water churns, indicating the tumultuous yet orchestrated motion of molecules in transit. These microscopic interactions serve as the foundation for the convection currents we observe. As water continues to heat, the phenomenon becomes even more pronounced, showcasing an elegant dance of particles governed by the laws of thermodynamics.

The principles of convection extend beyond the confines of a kitchen. On a grander scale, atmospheric convection plays a pivotal role in meteorology. The Earth’s atmosphere undergoes similar processes wherein solar radiation warms the surface, leading to localized thermal gradients. In turn, these gradients foster vast convection currents that influence weather patterns, cloud formation, and even storm systems. As warm air rises, it creates zones of low pressure; conversely, cooler air descends to fill these vacuums, fostering wind and contributing to the dynamic behavior of our climate.

Delving even further into the earthly realm, let us explore how convection is integral to oceanic currents. The world’s oceans are not static bodies of water; rather, they are a continuous movement of colossal proportions. The uneven heating of seawater causes the formation of convection cells in the ocean, which are inextricably linked to global climate systems. The interplay of warm surface waters with cooler depths leads to the establishment of thermohaline circulation—often described as the “global conveyor belt.” This circulation is vital for regulating temperatures across the globe, thereby affecting regional climates and ecosystems.

Another fascinating application of convection can be observed in the geological processes occurring beneath our feet. The mantle of the Earth is a viscous fluid layered beneath the rigid crust, and its convective currents are responsible for the movement of tectonic plates. When materials in the mantle are heated by the core, they rise toward the surface, where they cool and subsequently sink, creating a cyclical pattern that drives continental drift. This exquisite mechanism has profound implications: it is responsible for earthquakes, volcanic activity, and the formation of mountains, illustrating the sweeping power of convection in reshaping the planet’s landscape over eons.

The reverberations of convection are also present in the realm of engineering and technology. For example, designers of heating systems and electronic devices must consider convection currents to ensure efficient thermal management. In forced convection systems, fans are employed to enhance the flow of air or liquid, effectively preventing overheating and ensuring optimal performance of components. Designing systems that harness convection is not only a matter of efficiency but safety, underscoring the practical applications of this essential physical phenomenon.

Moreover, convection is observable in our daily lives through the act of baking. When an oven is preheated, the heated air rises, creating hot zones that affect how evenly food is cooked. Convection ovens are specifically designed to utilize fans that circulate hot air, allowing for quicker cooking times and even browning. This aspect not only highlights the culinary impact of convection but also illustrates how understanding this process can transform ordinary cooking into a science, revealing deeper intricacies behind culinary success.

In navigating through these varied examples, it becomes evident that convection is not simply a scientific principle confined to textbooks or laboratory studies. Rather, it permeates the fabric of our existence, influencing natural systems, technological advancements, and everyday activities. This omnipresent phenomenon invites curiosity and awe, serving as a reminder of the intricate dance of particles that collectively orchestrate the world around us.

In conclusion, the world of convection offers an expansive view of how heat transfer operates within both natural and artificial systems. From the simple act of boiling water to the majestic movements of ocean currents and tectonic plates, convection is a powerful and captivating process that binds together disparate elements of science and our daily lives. As we continue to explore and understand the implications of convection, we unlock the potential to innovate, predict, and perhaps even alter the environments we inhabit.