Gaslighting, a term that has permeated popular culture, refers to a form of psychological manipulation in which an individual seeks to make another person doubt their perceptions, memories, or understanding of events. This phenomenon can manifest itself in various contexts, from personal relationships to professional settings. Exploring specific examples of gaslighting unveils the complexities behind this behavior and reveals deeper insights about why it captivates us so profoundly.

At its core, gaslighting aims to destabilize the victim’s reality. One prominent example can be found in romantic relationships. Imagine a scenario where one partner often criticizes the other’s emotions or reactions. For instance, if one partner expresses distress over a particular comment, the other may respond with, “You’re overreacting,” or, “You’re too sensitive.” While at first glance, these statements may appear benign or even protective, they serve a darker purpose: to invalidate the partner’s feelings, thus eroding their confidence in their emotional responses.

In the workplace, gaslighting can take on a more insidious form. A manager might routinely undermine an employee by claiming that their ideas are unoriginal or by taking credit for their contributions. Consider a situation where an employee presents a unique project proposal, only to find their boss presenting a similar idea the following week without acknowledgment. When approached about this apparent injustice, the employee is met with denial: “You must have misheard the conversation” or “I don’t remember it that way.” This dismissal not only fosters confusion but also cultivates an environment of distrust in one’s professional achievements.

Friends and family dynamics can also fall prey to gaslighting. Picture a family gathering where one relative continually brings up past mistakes of another, insisting, “You always mess things up.” Such persistent reminders create a narrative that colors the victim’s self-image. They may begin to feel as though they can do nothing right, leading to increased self-doubt and a distorted self-perception. The longevity of this form of emotional intimidation can have long-term effects on mental health and interpersonal relationships.

Moreover, gaslighting often thrives in morally ambiguous situations, where individuals may refuse to acknowledge their wrongdoing. A striking example can be seen in political contexts, where leaders might manipulate facts to diminish dissent. When a politician asserts, “Those statistics are fabricated,” in response to criticism of governmental decisions, they engage in gaslighting on a grand scale. Such rhetoric not only delegates doubt onto the populace but also creates a power dynamic that can lead to widespread societal confusion and helplessness.

The fascination with gaslighting narratives often stems from their psychological depth. On one hand, the perpetrator exhibits a profound lack of empathy, manipulating vulnerabilities for personal gain. On the other, the victim experiences an emotional labyrinth, struggling to carve out their truth against an onslaught of contradictory narratives. This dynamic raises compelling questions about human psychology and the lengths to which individuals will go to assert control. What compels a person to engage in such a calculated deception? In many cases, the gaslighter may grapple with insecurity themselves, projecting their issues onto others as a coping mechanism.

Additionally, societal factors play a pivotal role in shaping the gaslighting experience. Cultural narratives glorify certain power dynamics—whether in patriarchal structures or corporate hierarchies—often rendering the victim’s truth invisible. This perpetuates cycles of manipulation that can be immensely difficult to break. Understanding this societal context adds a layer of complexity; it reveals that gaslighting is not merely a personal failing but a systemic issue that has historical roots.

Victims of gaslighting often find themselves perplexed, questioning their own cognitive faculties. The emotional abuse can manifest in various symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and a pervasive sense of unworthiness. It becomes imperative for individuals who have experienced such manipulation to seek validation outside their immediate circle. Connections with empathetic individuals, such as friends or therapists, can provide the affirmation needed to reclaim one’s sense of reality.

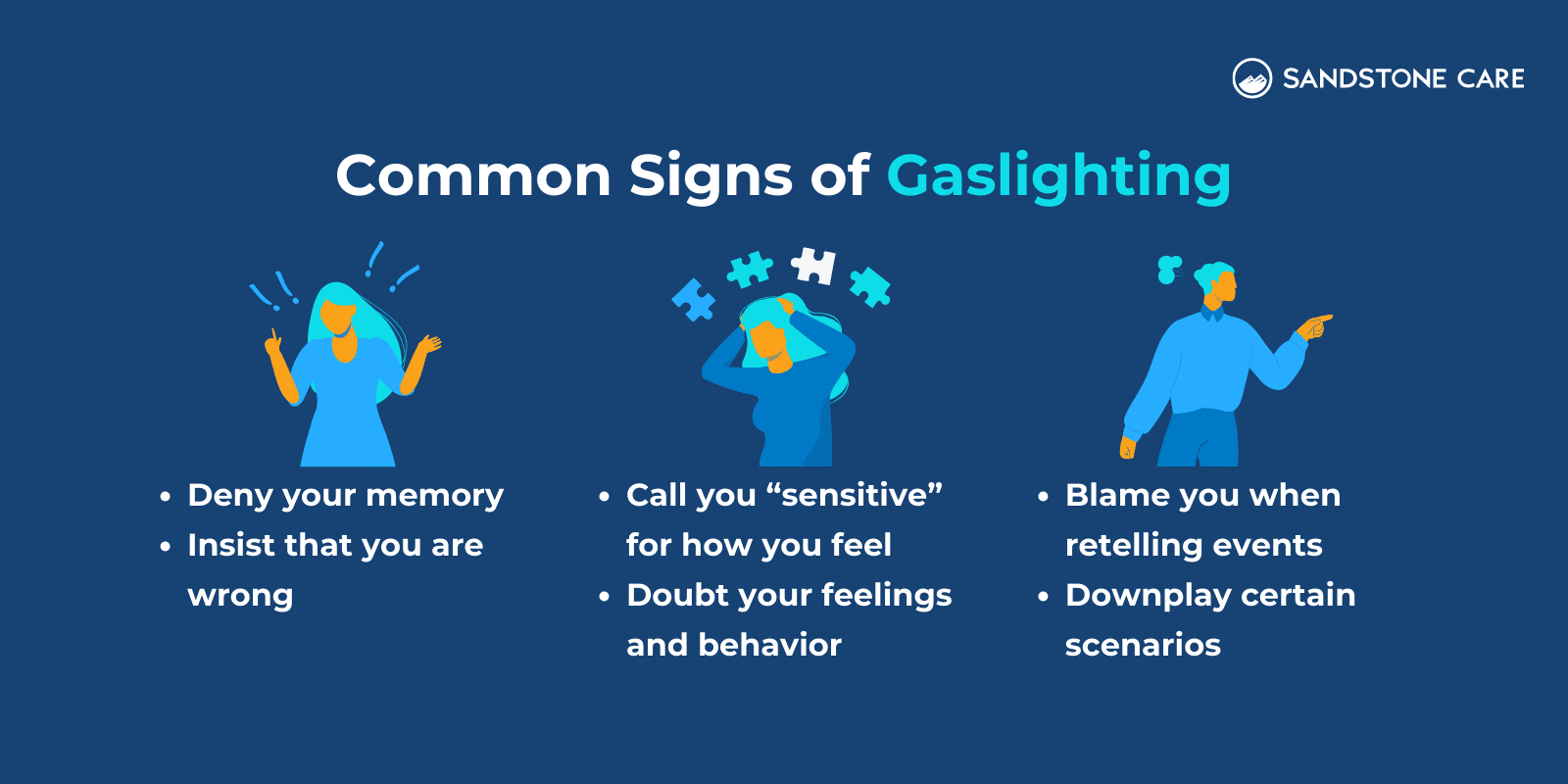

Recognizing the signs of gaslighting is crucial for prevention and healing. Familiarity with terminology and understanding the underlying manipulative mechanisms can empower potential victims to take a stand. Education surrounding emotional abuse can also serve as a preventative measure, helping society at large to combat this insidious behavior. By shedding light on the complexities of gaslighting, we contribute to a discourse that not only raises awareness but also cultivates resilience against emotional manipulation.

In sum, gaslighting is an intricate and multifaceted phenomenon that embodies both personal and social dimensions. The examples presented illustrate how this behavior can infiltrate various aspects of life, leaving victims disoriented and isolated. Understanding the nuances of gaslighting enriches our awareness of human interactions and empowers us to foster healthier relationships, whether in intimate partnerships, workplace environments, or the broader societal landscape. Ultimately, combating gaslighting requires a collective effort to value authenticity and emotional truth, thereby dismantling the mechanisms that enable such psychological manipulation.